(Prologue: This essay was originally written and published in 2016—nearly a decade ago. And yet, as I prepare to share it again today, it feels more urgent than ever.

We are living through an era of retraction. An era where the cultural ground Black artists have fought to claim is being eroded by backlash, censorship, and erasure. What’s under attack is not just representation, but authorship. Our right to narrate our own stories, to articulate our truths on our own terms, is increasingly threatened—whether by institutions that sideline us, markets that commodify us, or critics who misread and misframe our work.

In such times, it becomes imperative—revolutionary, even—for artists to write. To speak. To archive and assert our intent. Because when we don’t, others will. And their retellings too often distort, diminish, or erase the complexities we bring to our work and lives.

There’s a proverb that says: “Until the lion has its own historian, the hunter will always be the hero.” This piece—“Basquiat is a Grown-Ass Man!”—is a small act of lion’s history. A refusal to let the reductive, infantilizing language so often used to describe Jean-Michel Basquiat go unchecked. A demand that we honor the depth, strategy, and audacity in his work not as accident or instinct—but as intention.

In revisiting this piece, I’m reminded of how important it is that we not only make the work—but contextualize it. Document it. Name ourselves and our legacies clearly, before someone else does it for us. - June 2025)

Like Jean-Michel Basquiat, I have a healthy fascination with words. Whether written, spoken, rapped, or scrawled across the surface of a canvas—language, for me, is first and foremost a medium. And, as was the case with Basquiat, a visual medium. The ability to manipulate words, transform or subvert their meaning, repurpose them, reimagine them, have them do your bidding—that is the work of a master, an alchemist, a shaman. Wordsmithing is not a pedestrian sport. As such, words and language can be as volatile and treacherous as they are magical and beautiful.

It is ironic, then, that someone so masterful and adroit in his use of language is often described in terms that undermine him and the potency of his work. I find the language often used to describe Basquiat and his work deeply problematic—because, again, words are deliberate. They change things. How and where certain words are used, as well as who uses them and toward whom, is equally important. When terms like “child” or “primitive” are used to describe Jean-Michel Basquiat—an adult male and brilliant strategist—we begin a dangerous game of reductivism that distorts how his work is read.

So—what exactly are we saying, and what do we really mean when we refer to Basquiat as a child, radiant or otherwise? What do we risk missing or misconstruing when we reduce his mark-making to primitive expression? What do we fear confronting when we choose not to approach his work from a position that honors the gravitas and complexity it exhibits?

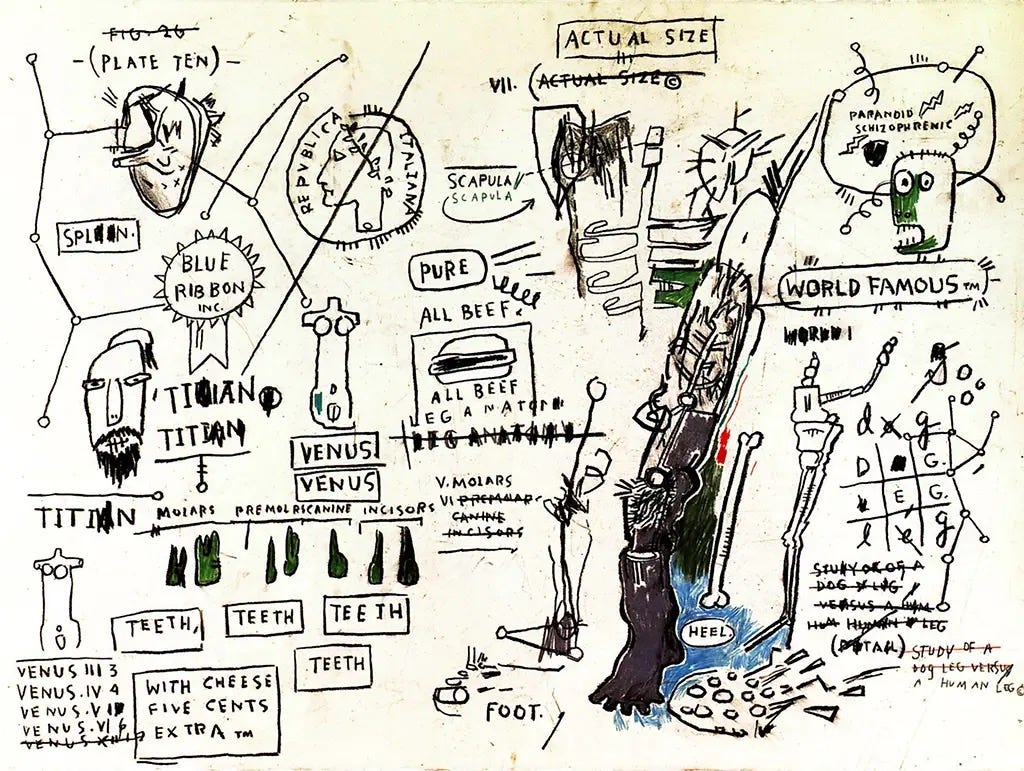

Is Basquiat’s work playful? Absolutely. Does it have an urgency? Without question. But neither of these attributes make his work childlike or primitive. Beneath the surface—and often in plain sight—are bold and complex ideas that belie the apparent simplicity of his texts. I use the term writing as opposed to drawing or painting because writing is, essentially, his medium. From the earliest moments of his career, it’s clear that writing was inseparable from Jean-Michel Basquiat’s practice.

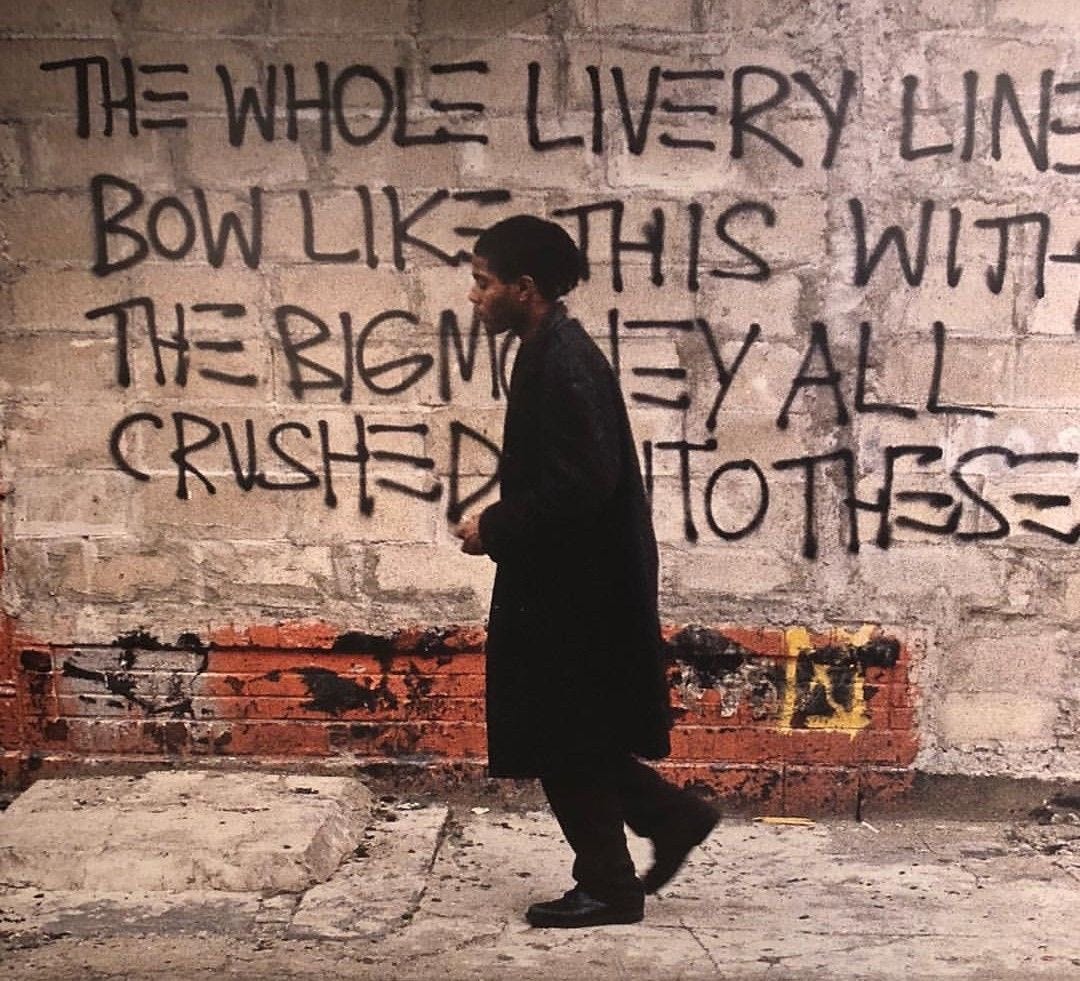

Take his SAMO© poetry, for example. It didn’t simply join the chorus of New York’s late seventies/early eighties graffiti scene—it changed the tune. Those early SAMO© writings are significant not only stylistically or as a record of Basquiat’s creative endeavors, but because they signaled the depth and brilliance of his artistic mettle. While many graffiti writers of the time were content to throw up their tags, Basquiat (as SAMO©) wielded the practice more abstractly. This wasn’t mere street art. The walls Basquiat painted—solo or with collaborator Al Diaz—were interrogations of modern society and, specifically, the art establishment. These interventions critiqued systems of exclusion: race, class, economics, accessibility. They were thoughtful and profound, prompting many—including Fab Five Freddy—to speculate that SAMO© was “just some sort of white conceptual artist.”

In his 1981 Artforum article “The Radiant Child,” Rene Ricard took great care to distinguish Basquiat from his graffiti contemporaries. Highlighting the emerging distinctions between street and fine art culture in the early ’80s, Ricard focused on SAMO©’s uniqueness, effectively introducing Basquiat to the art world. He noted that many of the artists in those massive group shows simply repeated their trademark tags—what he called “auto-logos.” They were accessible, easily commodified. “You are buying the label proper,” Ricard wrote, “the essential iconic self-representation.” But in Basquiat’s work, Ricard saw an “observable [art] history.” It was clear, even then, that Basquiat wasn’t just tagging; he was deliberately creating work that was as conversant with the downtown street scene as with Cy Twombly, Andy Warhol, Picasso, Matisse, Da Vinci, and other masters he had studied.

A closer reading of Basquiat reveals him as a conscious and conscientious selector, working in the tradition of hip-hop DJs and producers. His visual compositions sample art history books, medical texts, maps, conversations, newspaper clippings, magazines, novels, and jazz albums—the way J Dilla or Kanye West might sample old funk or R&B records. Sampling is tedious. It requires both deft and depth. Musically speaking, effective sampling demands intimate knowledge of particular canons, specific records, and nuanced timing. It is also a mode of survival—a means of assembling coherence, power, and beauty from the fragments left behind by cultural rupture.

Importantly, sampling isn’t copying. It is creating. The sample becomes another instrument or, in Basquiat’s case, a visual device used to compose new forms and alter perception. Though integral to hip-hop, this practice echoes survivalist strategies found throughout the Black diaspora—where remixing, repurposing, and reimagining have long served as tools of resistance.

This is not the work of a child.

In his catalogue essay for Basquiat: The Lost Notebooks, curator and Basquiat scholar Dieter Buchhart writes, “Basquiat’s drawings almost challenge the viewer to rap them aloud. His paintings, with their combination of pentimento, acrylic paint, oil sticks, and collage, create a form of painted hip-hop, with fragments of text playing a critical role as samples. And throughout the work, the artist’s intense critique of contemporary culture parallels hip-hop’s subject matter” (p. 38).

But Basquiat’s critique doesn’t merely parallel hip-hop—it is hip-hop.

Perhaps this incongruence is the most troubling. If we consider Basquiat through the lens of hip-hop, would we still call him a child? The performance of masculinity remains a hot topic in hip-hop. Despite the youth of many rap artists, we still associate rap—the commercial outgrowth of hip-hop culture—with an assertive, often hyper-masculine Black identity. From its earliest days, hip-hop has offered a public, political, and cultural space for dissidence.

If we read Basquiat’s masculinity and maturity through this lens, his critiques of contemporary culture become more dangerous, more incisive, more remarkable. Perhaps it is easier—safer—to accept the art world’s framing of Basquiat as a “radiant child.” A child is less threatening. But words matter. Words are matter. And what we speak becomes real.

There are serious consequences when we reduce Basquiat’s masculinity to that of a child or primal figure. We strip him of his agency and intention, dulling the edge of his critiques. We miss the opportunity to engage his work fully—including its most difficult, confrontational, and aggressive political truths. Infantilizing Basquiat diminishes his manhood and practice.

Recognizing Basquiat’s manhood—his sharp critique of racism and classism, his deep ties to hip-hop, art history, and art world politics, and his complex, cerebral relationship with language—offers a fuller, more radical understanding of the artist, his work, and his enduring legacy.

Indeed, most will blindly see and reference through the lens of the "Radiant Child" by Rene Ricard because it was published from an established art publication. The late, Greg Tate, replied to this early definition with his 1989 Village Voice article, “Nobody Loves a Genius Child." But he was also riffing Langston Hughes's poem, Genius Child (1958).

Author, poet, bell hooks also shared her reflection of Jean Michel Basquiat in the article, "Altars of Sacrifice, Re-membering Basquiat" (1993.) hooks reflected on the poly lingual Basquiat and his intersectional approach to the rhythm of 1980s art world cannibalism. "I won't even mention those scholars who dismissed his contributions."

MTV also vilified and reduced singer Michael Jackson in the 1980s by referencing him as "Jacko" their way of saying short for Jackson. Jacko sounding very similar to Jackal was a fitting name that MTV used during the first half of the 1980s decade of music video-Racial segregation.

All that is sacred in Basquiat's work is still veiled though.. the ritual, spiritual and necessary aché.

Thanks for sharing this essay! I’ve always been out off by the infantilizing language ascribed to Basquiat’s work and life. I was a teenager in the ‘80s and just learning about art from a traditional perspective (landscapes, still life, etc…) and didn’t have a handle in contemporary work at the time. Later, in the early ‘90s, after widening the scope of my training and knowledge, I gained a solid appreciation for what Basquiat was making and what he went through in the ‘80s.

The use of “primitive” and “child” as descriptors for he and his work always irked me. It was always used as “less than”, the same as how the work of other Black artists was written about. Instead of paying attention and going deeper into the work and the cultural signifiers that were embedded, most critics erred on the side of surface interpretations of his work. It was easier for them to jump on the bandwagon of “bringing the streets to the gallery” because they didn’t have the depth to go further or they didn’t care to do so because he was Black.